Getting back to some George Saunders stories here.

This story feels like a roller coaster of contradictory thoughts. The constant banter of Roosten's inner thoughts makes it difficult to follow the story, but I am going to give it a shot. Roosten is the owner of a store called Bygone Daze, a shop that sells vintage collectibles. Roosten is volunterring in a strange charity event called LaffKidsOffCrack. Along with Larry Donfrey, Roosten is going to be auctioned off to the highest bidder. Roosten and Donfrey both saunter down a runway, presumably to increase their chances of being bid on. After Roosten does his runway walk, he walks to the "cardboard jail" where he has "his own barred window". Once this bizarre spectacle is over, Roosten retires to the changing area where, in a fit of jealous anger, he kicks Donfrey's keys and wallet underneath a "stack of risers."

Roosten drives "through the town where he'd lived his whole life" while his mom talks to him from heaven. Roosten feels guilty about Donfrey's keys so he envisions an alternate timeline where he goes back to the event and helps Donfrey find his keys and wallet. He even envisions himself eating dinner with the entire Donfrey clan. None of this is actually happening.

Roosten reaches his shop across the street from a junkyard where "hoboes hung out." Roosten imagines himself beating up a homeless man with "ghoulish" teeth and red eyes. Roosten frames this as a valuable lesson for the homeless man. Instead Roosten and the homeless man exchange weak smiles and go on their ways.

Summary

Roosten drives "through the town where he'd lived his whole life" while his mom talks to him from heaven. Roosten feels guilty about Donfrey's keys so he envisions an alternate timeline where he goes back to the event and helps Donfrey find his keys and wallet. He even envisions himself eating dinner with the entire Donfrey clan. None of this is actually happening.

Roosten reaches his shop across the street from a junkyard where "hoboes hung out." Roosten imagines himself beating up a homeless man with "ghoulish" teeth and red eyes. Roosten frames this as a valuable lesson for the homeless man. Instead Roosten and the homeless man exchange weak smiles and go on their ways.

Analysis

The narrator of this story cycles between a third person detached POV and direct access to Al Roosten's real thoughts. I would argue that the focus of the story is the distinct voice representing Roosten's inner thoughts. The voice is contradictory. It goes from one thought to the exact opposite immediately. I would characterize it as neurotic and possibly unstable. Roosten typically envisions himself performing outrageous feats but his real-life behaviour is contained and measured. The frankness of the third-person narrator brings the reader closer to Roosten, making him a more sympathetic character. There's a tension between Saunders's view of Roosten as disgusting and the narrator's desire to make Roosten seem pitiful and sweetly stupid.

Donfrey acts as an interesting foil to Roosten. Donfrey is much more successful and handsome than Roosten and Roosten even admits that Donfrey is a "good guy". The narrator remarks that Donfrey and Roosten are "twin pillars of the local business community," yet appears to have a much better life. Donfrey is simply and upgraded version of Roosten in every way.

The voice of Roosten's mother is an interesting aspect of this story. It's telling that the dead mother is still speaking so coherently and frequently in Roosten's head. We can add hearing voices to the list of Roosten's issues. The mother is giving and realistic. She tells Roosten that his "moral courage" is his most important trait.

I am surprised at how much there is to examine in this story. On the first reading, it was hard to track the story's plot while following the crazy statements of Roosten's inner thoughts. Once I became comfortable with this structure, it became easier to find the meaning in this story. It will be fun to revisit this story and find even more insane ways that Saunders creates meaning. There's a lot to chew on in Roosten's thoughts and in the story's unique setting.

|

| An illustration of Al Roosten and Larry Donfrey from the New Yorker. |

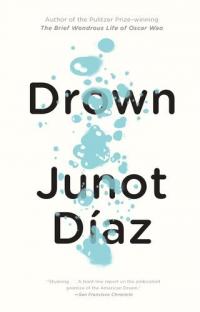

BUY HERE:

https://amzn.to/2P4mMp7

https://amzn.to/2P4mMp7